Bison in Indian Country

Several Native American reservations have had bison herds of various sizes for decades. Many have been periodically augmented with bison from federal parks and refuges. Information about management of Native American herds has not been widely available; but indications are that at least most herds have been managed much as livestock in commercial herds. These bison are being domesticated. Recently, some reservations have established “cultural” herds, separate from their commercial herds. Again, management practices for cultural herds are not publicized, probably vary among Tribes, and could change over time with Tribal needs and politics. A contribution of Native American plains bison herds to restoration of wild bison is, at best, uncertain. Native Americans have unique economic, nutritional and religious/cultural needs for bison. As separate nations, management of their bison, according to their needs, is their exclusive right. We wish them well. Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks released a draft Environmental Impact Statement in 2015, proposing a “programmatic” plan for Bison Conservation and Management. The EIS would determine whether bison would someday be restored on lands of willing landowners, on Tribal lands, or on a broader, more diverse landscape, nothing more. The EIS languished for 5 years. Alternative 3, Restoration of a publicly managed bison herd on Tribal lands, is described in Chapter 3, available on the FWP website. It refers to developing a FWP/Tribal Memorandum of Understanding on specific management practices and responsibilities for a “public” herd on Tribal lands. In a 2020 Record of Decision, FWP requested the public to submit proposals for bison restoration. Currently, several major conservation organizations have been expanding their programs to encourage and support plains bison restoration on Tribal lands in Montana. In contrast, these organizations have been reticent to support bison restoration on and near the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge. None have agreed to be listed as supporting the two goals of the Montana Wild Bison Restoration Coalition.

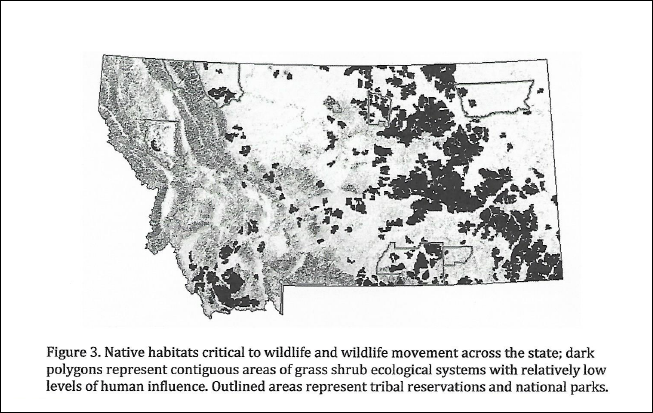

Such a decision would be based mostly on political considerations. It would not be based on which EIS alternative would provide (1) the most and broadest distribution of diverse benefits from wild bison to all Montanans; or (2) the best bison herd in the best location for conserving truly wild plains bison. Montana’s benefits from a Tribal/public bison herd on a Reservation would depend upon negotiations for a Memorandum of Understanding with the Tribe. The EIS specifies only that “bison hunting and viewing access would have to be allowed within tribal lands.” It also commits the state to monitor for bison diseases. Details such as herd size, sex-age composition, periodic handling of bison, determination and distribution of harvestable surpluses, hunting seasons, “any financial incentives for allowing public access”, habitat monitoring and the lifespan of the MOU would be negotiable. These details will determine benefits to non-Indian Montanans and also the wildness of the bison herd. Hopefully, the FWP EIS process will not irrevocably commit to alternative 3 with all these uncertainties. In contrast, restoration of public, wild bison on and near the CMR National Wildlife Refuge (alternative 4 of the EIS) has far greater potential for benefitting all Montanans and for conserving truly wild bison. With alternative 4, bison would be big-game wildlife under Montana law. All management issues would not be limited and complicated by negotiations with another Nation. Benefits to Montanans could be maximized. Also, opportunities to develop a large, mobile, self-sustaining and productive wild bison herd are far greater on and near the CMR NWR than on any Tribal Reservation. A genetically-adequate herd requires at least 1000 animals, probably more in the long-term. Mobility is a basic wild characteristic of plains bison. A large, mobile herd requires a large landscape. Fig. 3 in the EIS (below) clearly shows far more abundant potential bison habitat on and near the CMR, compared to the Reservations. Moreover, this area contains the most, contiguous public land.

The Coalition supports enhancing cultural bison herds on Native American Reservations. Herds should be established and managed according to Tribal needs. Collaboration with the state for mutual public benefits is desirable, but not necessary. But more bison in Indian Country likely will not restore truly wild bison for conserving the species; and it will not absolve Montana from our obligation to provide public, wild bison on public lands for the use and enjoyment of future generations of Montanans. Bailey, J. A. 2013. American

plains bison” Rewildling an Icon. Sweetgrass Books, Helena,

Montana. 238 pp. |

Site designed and maintained by Kathryn QannaYahu Kern