Bison

Hunting and "Wildness"

Throughout glacial and interglacial periods, natural selective forces affecting these bison included intra- and inter-species competition, predation, disease, and climate, including its associated effects on vegetation and forages.But selection changed near the end of the ice age when bison began to evolve into the modern species, Bison bison, with integrated adaptations of anatomy, physiology and behavior.

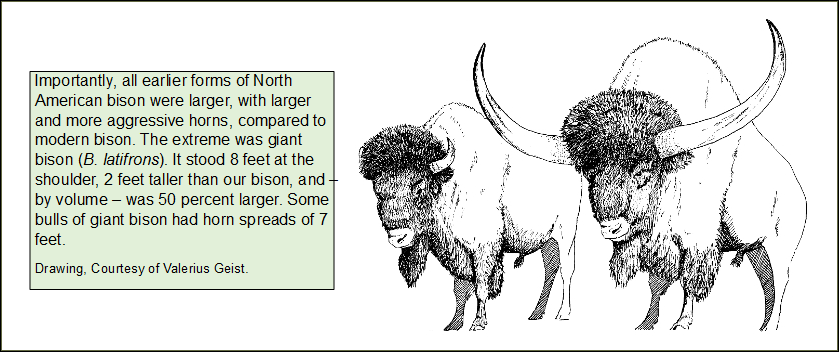

The large size of early bison suited ice-age environments, but was especially a response to predation. These bison lived with at least 13 species of large and/or formidable predators. There were gray wolves, dhole and dire wolves, short-faced bears, grizzly and black bears, sabertooth and scimitar cats, American lions, jaguar, cheetah, puma and men, though humans were late to become abundant. Most dangerous among these non-human predators was the short-faced bear, which dwarfed grizzly bears. Short-faced bears stood 6-feet tall at the shoulders. Their long legs were designed for running down large prey. The large size and large, aggressive horns of ice-age bison must have been largely an adaptation for predator defense. Presumably, bison assumed a social “stand and defend” posture, with smaller, younger bison shielded behind the larger animals. We still see glimpses of this behavior in modern bison. However, at the end of the ice age, 8 of the 13 dangerous predators went extinct. This diminished the value of a stand-and-defend predator strategy. At the same time, a new predator showed up – humans. These new predators used and threw spears. A stand-and-defend strategy was useless against them. These events created a major shift in bison evolution, a behavioral change from predator-defense to predator-escape. The evolution of Bison bison began. Modern bison are smaller than ancestors of their past – and probably faster with more stamina. The dominant character of bison shifted from “big and bad” to great mobility. This evolved change in behavior required congruent changes in anatomy and physiology. Moreover, the new characteristic of great mobility offered new possibilities for habitat use in response to seasonal and weather-related variation in the environment. All the evolved characteristics of modern bison, for dealing with both the threats and opportunities of their environment, are congruent with the characteristic of great mobility. It seems the mobility strategy was quite effective against pedestrian human predators, allowing 30-or-more million bison to persist in North America. In contrast, the ability of bison to withstand horse-mounted hunters was not tested for long. Clearly, clever horse-mounted Native Americans were sometimes able to kill very large numbers of bison in early historic times (Bailey 2016). Early accounts indicate that mobility was an important bison response to human hunters. Both Native-American and Euro-American hunters used caution not to disturb bison herds until a full contingent of hunters could be brought up for a “surround”. Otherwise, the bison were expected to escape over a long distance. Clearly, human hunting has been a dominant factor in the evolution of modern bison. Thus, there is no basis for considering hunting as “unnatural” for the species. Yet the culling effects of modern hunting may weaken or replace all other forms of natural selection. This threat is exacerbated in today’s bison herds for which intensive management (artificial selection) and small-population effects also weaken and replace natural selection. Excessive levels of hunting, or of any human-applied culling, can impel bison herds away from wildness toward domestication, especially in small herds. (See also the biological definition of wildness on this website.) Given the above, how do we judiciously apply hunting to bison herds for which maintaining wildness is a goal? Because bison herds vary greatly in size, environments and management objectives, only general principals are offered here.

It is desirable to retain hunting as a form of natural selection on any bison herd for which maintaining wildness is a goal. But attempts to use harvest as a tool for maximizing bison production, by controlling herd size and sex-age composition, is an application of livestock management – jeopardizing wild characteristics and leading to domestication. For purposes of wildness, it is desirable that some bison succumb to types of natural selection other than hunting. This will be easiest to achieve if the herd is large, permitting considerable human harvest as well as other forms of mortality. By contrast, with a small bison herd, negative genetic effects of small population size (inbreeding and genetic drift) would augment the artificial components of human harvest in weakening and replacing all other forms of natural selection.

Bailey, J. A. 2013. American Plains Bison: Rewilding an Icon. Sweetgrass Books, Helena, MT. 238 pp, _____. 2016. Historic distribution and abundance of bison in the Rocky Mountains of the United States. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 22:36 – 53.

|

Site designed and maintained by Kathryn QannaYahu Kern